Homecoming for Seniors

Continuing-care retirement communities can provide a pleasant communal living experience. But retirees should research costs and services before moving in.

Patty and Bill Lawson lived in an expansive Pasadena home before Bill began suffering health problems.

“All of a sudden we realized that we were mortal after all,” Patty says. “We had a big piece of property–about three-quarters of an acre–and all these cymbidium orchids that were wonderful but a tremendous amount of work. There comes a time when you realize how difficult it would be to handle things on your own.”

That was nearly a decade ago. After spending several years researching and considering the idea, the Lawsons became part of a growing cadre of senior citizens who move to a continuing-care retirement community, a little-known and often misunderstood type of living arrangement designed solely for people over the age of 60.

Roughly 594,000 seniors live in CCRCs, up from an estimated 350,000 in 1994, according to the American Assn. of Homes and Services for the Aging in Washington. And whereas these homes were once relatively rare–a scattered number were offered mainly through churches and fraternal organizations–there are now about 2,100 continuing-care communities nationwide, with at least one in every state. Some states–most notably California, Pennsylvania, Florida, Illinois and Ohio–are home to dozens.

And with the rapid graying of America–the fastest-growing segment of the U.S. population is age 85 and older–the industry is expanding by leaps and bounds.

Still, few people know what a CCRC is and what it might have to offer.

“We get a lot of kids who really don’t understand where Mom and Dad are going. They’ll say, ‘Gee, Mom, why would you want to do that?’ ” says Randy Stoll, president and chief executive of Mt. San Antonio Gardens, a Pomona-based life-care community. “But half the time after they come out and see our campus, they want to know how old they have to be to get in here.”

The confusion is not surprising. While the term “continuing care retirement community” may conjure up images of nursing homes, the typical CCRC is more like Leisure World with health care, or a college campus for the gray-haired. But as with colleges, there are huge variations in costs and services.

Some CCRCs provide pleasant retirement living with a health-care component that eliminates the worry about the affordability of nursing care. Others are less congenial, less comprehensive and more costly.

“Once you’ve seen one continuing-care retirement community, you’ve seen one continuing-care retirement community,” quips Robert Greenwood, a spokesman for the Homes and Services for the Aging group. “It’s a fairly flexible model.”

What they all have in common is community living–residents usually have their own homes or apartments but share dining and recreational facilities–and on-site access to health care. Although there are no set participation rules, most have check-in requirements aimed at ensuring that a resident’s unexpected medical problems won’t go unnoticed for long. Financially, there is usually a fairly large upfront payment required, as well as monthly payments that cover the cost of services.

Beyond that, however, the variations are great.

Entry fees, for example, can range from a few thousand dollars to several hundred thousand dollars, depending on the CCRC and the type of housing the applicant chooses. In a few cases, the upfront payment is also contingent on the applicant’s age, because the residents aren’t actually buying their housing–they’re merely using it for the remainder of their lives. The shorter the expected life span, the smaller the upfront payment.

The monthly payments also vary widely depending on the type of facility and what the payments cover. In some CCRCs, for example, the monthly payments remain fairly constant and cover all services the resident could use, ranging from home maintenance to health care. At others, they are contingent on how many services are used.

These services can include daily meals, housekeeping, transportation, entertainment and personal services, which can range from help with daily tasks to having a painting hung to skilled nursing care. So, for example, a person who used only the dining, entertainment and housekeeping services in the “independent living” section of a “fee for service” CCRC would pay substantially less than a person who required skilled nursing care.

In addition, some CCRCs promise to take care of residents for life–no matter how old, ill or poor they become. Should financial hardship prevent them from making their monthly payments, they could apply to the community’s “benevolent fund,” which would help cover the portion the resident was unable to pay. At other CCRCs, you might be guaranteed a home only for as long as you continue to pay.

The health services offered can also range from sparse to comprehensive, so seniors would be wise to investigate the community carefully before signing up. The services provided are usually clearly spelled out in the contracts that applicants are given. In addition, most good CCRCs encourage–some even require–applicants to visit the community and chat with residents numerous times before joining. Stoll says that’s for the good of both the applicant and the community, because a congenial atmosphere can’t be maintained unless residents work together and participate in activities.

In any event, seniors should carefully consider the type of services they’d prefer and then look at several CCRCs to determine which offers the best mix at the most attractive price.

“This is a big decision, not something you could do as a snap judgment,” Lawson says. “It behooves you to do some research before you commit yourself.”

Kathy M. Kristof is a syndicated columnist and author of “Kathy Kristof’s Complete Book of Dollars and Sense.” Write to her in care of Personal Finance, Business Section, Los Angeles Times, Times Mirror Square, Los Angeles, CA 90053, or e-mail kathy.kristof@latimes.com

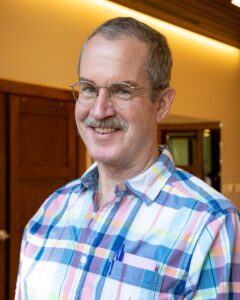

Jane Hurd is a Gardens resident, she was born & raised in a small town in Arkansas. After she received her BA from the University of Arkansas she moved to California and taught seventh grade English in Porterville CA. After two years she moved to Los Angeles and worked for the Department of Health Services and pursued a master’s degree in public administration from USC. She served as CEO for two Los Angeles area hospitals. She continues to consult as an executive coach for CEOs of healthcare companies. She has served on several boards including Mutual of America Insurance Company, YMCA of Metropolitan LA, LA Visiting Nurses Association and Inland Empire Girl Scouts. Jane is an award-winning author and plays several musical instruments. Here at the Gardens, Jane is part of the newly formed Bequest Committee, as well as many other groups through the Gardens Club.

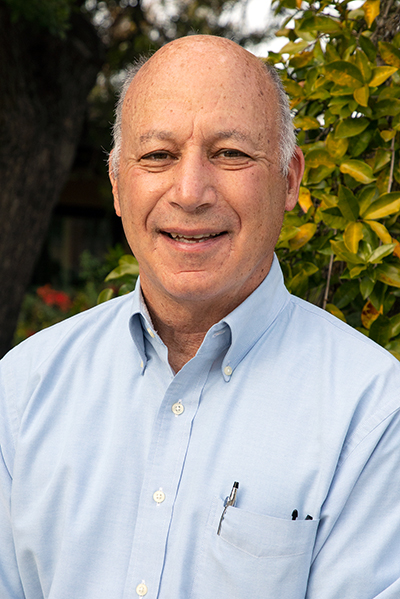

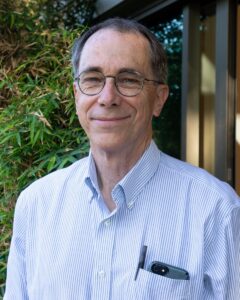

Jane Hurd is a Gardens resident, she was born & raised in a small town in Arkansas. After she received her BA from the University of Arkansas she moved to California and taught seventh grade English in Porterville CA. After two years she moved to Los Angeles and worked for the Department of Health Services and pursued a master’s degree in public administration from USC. She served as CEO for two Los Angeles area hospitals. She continues to consult as an executive coach for CEOs of healthcare companies. She has served on several boards including Mutual of America Insurance Company, YMCA of Metropolitan LA, LA Visiting Nurses Association and Inland Empire Girl Scouts. Jane is an award-winning author and plays several musical instruments. Here at the Gardens, Jane is part of the newly formed Bequest Committee, as well as many other groups through the Gardens Club. Jay Labinger is a Gardens resident, he was born and raised in Los Angeles, CA. Jay received his Bachelor of Science in Chemistry from Harvey Mudd College. He attended Harvard University where he earned a Ph.D. He was an Assistant Professor of Chemistry at the University of Notre Dame. His career has included positions with Occidental Research Corporation & Atlantic Richfield. He is the Administrator of Beckman Institute at the California Institute of Technology as well as a Faculty Associate in the Chemistry Department. He enjoys reading, playing the piano, tennis and traveling. He has published books on the history of chemistry, sociology of science and literature & science. Here at the Gardens, Jay is part of the Conservation & Sustainability Committee the Green Fund as well as many other groups through the Gardens Club.

Jay Labinger is a Gardens resident, he was born and raised in Los Angeles, CA. Jay received his Bachelor of Science in Chemistry from Harvey Mudd College. He attended Harvard University where he earned a Ph.D. He was an Assistant Professor of Chemistry at the University of Notre Dame. His career has included positions with Occidental Research Corporation & Atlantic Richfield. He is the Administrator of Beckman Institute at the California Institute of Technology as well as a Faculty Associate in the Chemistry Department. He enjoys reading, playing the piano, tennis and traveling. He has published books on the history of chemistry, sociology of science and literature & science. Here at the Gardens, Jay is part of the Conservation & Sustainability Committee the Green Fund as well as many other groups through the Gardens Club.